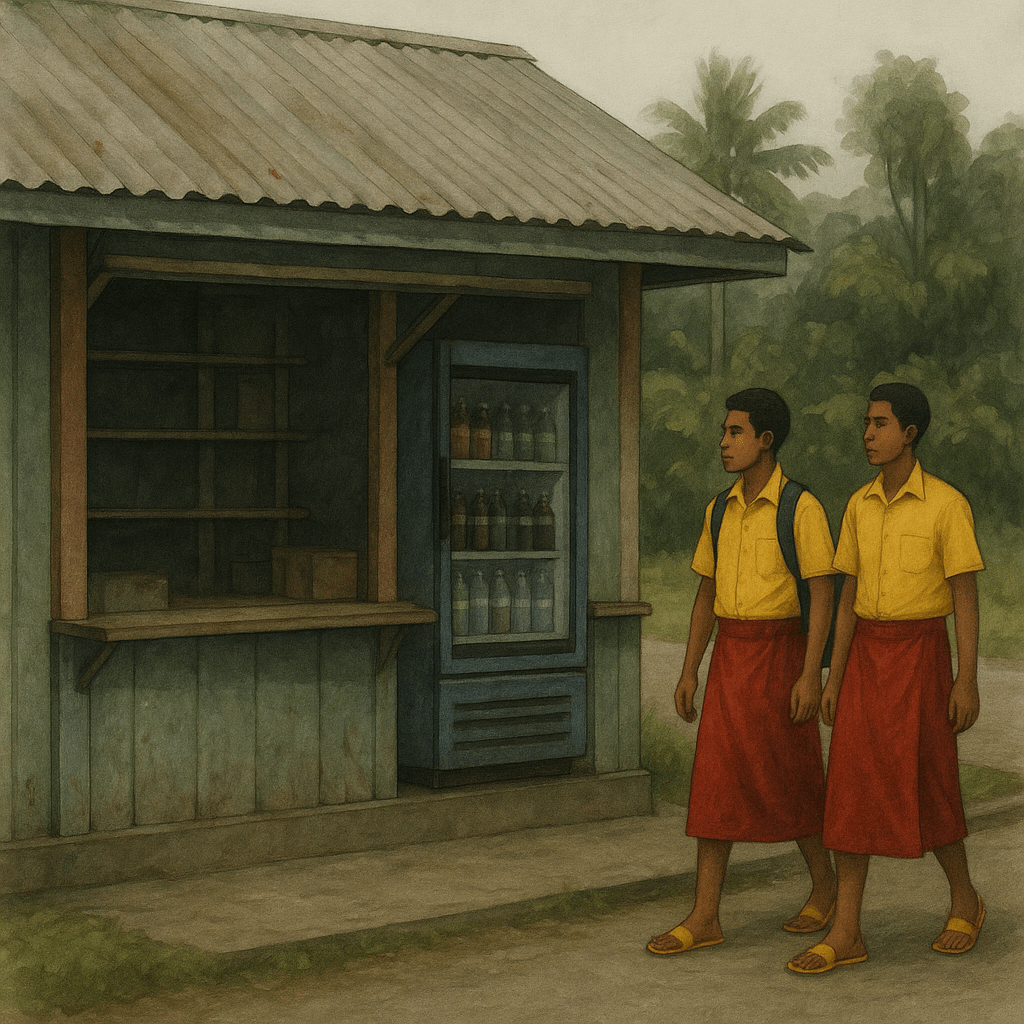

The refrigerators hummed in the early morning as I lifted the heavy wooden flaps on the store counter. The store always felt like a prison — you could never go far. My mother left in the car to do the fa‘akau (shopping). She told me she needed me here today. She didn’t ask if I had anything important; by then I was tired of asking for things they would only refuse. Outside, I saw kids in pressed red and yellow uniforms walking up the street, their voices bright, making their way to our graduation.

By noon, the graduation was on television. I watched my classmates sway to Vitamin C’s Graduation, their faces lit with the future. When my father came by, he caught me watching. He laughed and said it wasn’t like I’d won a prize anyway — I was more useful here, in the store, than in town being a ka’a (young person who enjoys going out).

The elections were near, and with my father a candidate, the house and store filled with visitors from my grandfather’s village. He called them family. To me, they were leeches. I looked at the shelves — half empty now, stripped by campaign promises. Strangers came to our door asking for money for their children’s fees and uniforms. My parents always helped them. Meanwhile, my siblings and I wore the same faded, torn uniforms, our own fees pushed aside for nobodies who did nothing for us except take. My parents said the fa‘aSamoa was about humility — sharing what you have, giving away the good, keeping the bad for yourself. What it really showed us was their willingness to prioritize strangers over their own children.

By the time my mother finally came back that afternoon — later than she’d promised — I was already over it. I slipped into the house, hoping to sit in my room for a while, but the place was thick with visitors shoving their faces with whatever they could and I couldn’t disappear. I refreshed myself, then walked back to the store like she asked. The counter flaps, the refrigerators, the empty shelves — all waiting, exactly as I’d left them. The day had ended, but nothing had changed.

Some might ask why I don’t try to see this day from my parents’ perspective now that I’m older. The truth is I always did. Growing up, I bent myself into their struggles, tried to be the perfect daughter because I knew how hard things were. I played the role of housewife and mother when my own mother had no time. But I’m tired now. I’m taking back what should have been mine — including the right to tell this story from my own perspective.

Leave a comment